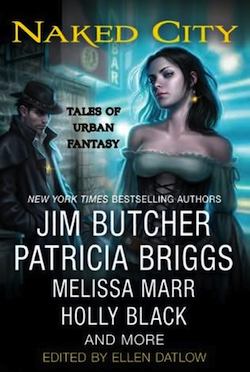

This is the year of the urban fantasy anthologies—Welcome to Bordertown, edited by Ellen Kushner & Holly Black (reviewed here); the upcoming Gardner Dozois & George R. R. Martin anthology Down These Strange Streets; and The Urban Fantasy Anthology edited by Peter S. Beagle & Joe R. Landsdale, for example—and Ellen Datlow’s Naked City is one such contribution to what could be taken as a canon-making venture shared between several editors with different visions of the genre. After all, the biggest question about urban fantasy tends to be “what’s urban fantasy, really?”

In Datlow’s introduction to Naked City, she explains it as a subgenre that originated through books like the first Borderlands anthologies, Emma Bull and Charles De Lint’s work, et cetera: stories where the city was of paramount importance to the tale, where the urban was inextricable from the fantastical. She also acknowledges that it’s grown to include further sub-subgenres like supernatural noir, paranormal romance, and all the things in between, plus the texts that fit the original context. It’s a good, short introduction that gives a framework for the kinds of stories that will follow in the anthology—a book whose title is a reference to an old television show, “Naked City,” as well as a crime documentary, as well as the idea of stories stripped down to show what really goes on in these urban centers. That multi-referential title is a fair indicator of the variety that follows in the text itself.

This anthology has both stories set in existing universes—the Jim Butcher, the Melissa Marr, the Ellen Kushner, and the Elizabeth Bear, for example—and purely stand-alone tales; the stories range from the mystery-solving supernatural noir end of the scale to horror to humor to a touch of steampunk. Naked City is an anthology of solicited stories, all original with no reprints, so each tale is fresh. (This is especially fun with the series tie-ins, as they’re each new looks at the worlds in question.) It’s a nicely varied collection that touches on most corners of what “urban fantasy” has come to mean to today’s readers, and Datlow’s deft-as-usual hand at arranging a table of contents means that there’s never a feeling of repetition between stories.

Naked City is also evenly balanced in terms of quality; I enjoyed nearly every story—except one, but we’ll get there—though I’ll admit I wasn’t particularly blown away by any of them. Let that not be a deterrent of any kind, though. The stories are, to the very last page, eminently readable, entertaining and well-written; each offers something different to the reader in terms of that crucial urban setting and an interpretation of what that means for the characters. That’s what I ask from any given anthology, and Datlow’s Naked City delivers. Bonus, it has a few queer stories.

One of my favorites of the collection is Peter S. Beagle’s “Underbridge,” a scary story that’s as grounded in a contemporary urban setting as it is the supernatural. The lead character, a failure as an academic whose career has spiraled down to running from place to place to fill in temporary positions without any hope of achieving tenure track, is at once deeply sympathetic and also hair-raisingly off his head, by the end. The location, the walks he takes down the streets, the neighborhoods he commentates upon, and his surroundings—especially that Troll statue—are intrinsic to the story; they bring it to life and make readers feel as though they, too, have stumbled into something horrible and magical. It makes the ending that much more wild and uncomfortable.

Delia Sherman’s tale of an Irish immigrant and the pooka who owes him a life-debt, “How the Pooka Came to New York City,” is another great story, one of the best in the book. The historical context, the dialect and the emotional heft of the tale are all spot-on, vibrantly alive and believable. The shifting viewpoint of the tale, from the pooka to the young Irishman and back, works perfectly to tell the story as they explore the developing, bustling New York City, which is as real to the reader as they are. Sherman does a fabulous job capturing a historical moment while still telling a fantastical story with the fae and the mortal intersecting in the strange, big city.

“Priced to Sell” by Naomi Novik is so very amusing that it’s also one of the stories that stuck with me after finishing the book. Her supernaturally strange Manhattan is believable in the extreme—it’s all about real estate, and co-op boards, and undesirable tenants. The young vampire with the crap references, Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, and the cursed wall of the otherwise-awesome townhouse; it’s all hilariously vivid. I deeply enjoyed this story for the lightness it injects into the volume, as well as its idiosyncratic portrait of a city filled with the fantastic.

Nathan Ballingrud’s “The Way Station” is another story of the sort I’ve come to expect from him: emotionally intense, riveting, and deeply upsetting in many ways. It deals with loss, with the aftereffects of Katrina on a homeless alcoholic who’s haunted by the city itself before the flood, and in doing so it’s wrenching. The strangeness of the haunting—city streets in his chest, floodwater pouring from his body—creates a surreal air, but the harsh reality of the world the protagonist lives in anchors that potential for the surreal into something more solid and believable. It’s an excellent story that paints a riveting portrait of a man, his city, and his loss.

Last but not least of the stand-alones that left an impression on me is Caitlin R. Kiernan’s “The Colliers’ Venus (1893),” a story that is actually sort of steampunk—dirigibles and a different evolution of the American west and whatnot—but that’s just a bit of skin on the outside. The tale itself is about the weird and the inexplicable, as well as paleontology and museums. The touch of the disturbing in the primordial thing in woman shape—time, in some ways—is handled perfectly with Kiernan’s usual brilliant prose. Each word of her story is carefully chosen to create a historical moment and to anchor the tale into a commentary on cities and their impermanence. It’s a very different angle than all of the other stories, which are focused directly on the cities themselves; this story instead makes a statement about the temporary nature of civilization itself. This sideways angle on “urban fantasy” is a great addition to the rest, and probably provokes the most thought of the lot.

As for the series-related stories, I’ve read all of the originating books except Marr’s Graveminder, and I enjoyed them all. (In fact, I had fun with the weird, weird dead world of “Guns for the Dead,” which will prompt me to read Marr’s novel.) The Butcher tale, set before recent events in the Dresden Files series, is a pleasant aside about baseball and the meaning of the game. It’s sweet. The Kushner explores something we haven’t seen before in the Riverside universe—how Alec ascended to be Duke of his House. It’s moving for someone familiar with the characters; I loved it, and read it twice in a row. My favorite of the bunch is the Bear story, “King Pole, Gallows Pole, Bottle Tree.” It’s set in her Promethean Age universe, which is possibly one of my favorite created worlds ever, so, well. It’s a One-Eyed Jack and the Suicide King tale, set in Vegas, dealing with memory, loss and identity. I adored it, but considering how fond I am of that series as a whole, that’s not much of a surprise. The mystery is good, the presence of the city is excellent, and the story is just so much fun.

The single story that I didn’t enjoy was “Daddy Longlegs of the Evening” by Jeffrey Ford. It didn’t feel particularly like urban fantasy in the sense of a story concerned with cities; it was a told-tale horror story, and I didn’t much care for it. The writing is just fine, as is to be expected from Ford, but the story itself simply didn’t work for me—it couldn’t hold my attention.

*

Taken as a whole, Naked City is absolutely worth reading for a fan of contemporary fantasies set in urban environments—or, urban fantasy, as we say. It’s also good for folks who might not be certain how they feel about the genre, as it offers quite a lot of looks at what it can and could be. The stories are, for the most part, great reading that effortlessly engages the imagination. They paint brilliant scenes of cities and the people—or, other things—that live in them. Datlow as editor is reliable as usual; I’m always satisfied after finishing a collection of hers.

Lee Mandelo is a multi-fandom geek with a special love for comics and queer literature. She can be found on Twitter and Livejournal.